SILVANA MOSSANO

Reportage udienza del 22 ottobre 2021

Inalare polveri fa male? Sì. Diffondere polveri dentro e fuori l’ambiente di lavoro è male? Sì. Ci sono precauzioni da adottare? Sì.

Lo scriveva chiaramente Heinrich Albrecht, viennese (1866-1922), nel suo poderoso «Trattato di igiene industriale» pubblicato nel 1898. «Tradotto dal tedesco in italiano» ha puntualizzato il dottor Stefano Silvestri, igienista del lavoro, con particolari competenze nel settore dell’amianto, già dipendente dell’Istituto di prevenzione oncologica della Toscana, con incarichi in commissioni ministeriali, consulente tecnico in diversi procedimenti giudiziari inerenti reati ambientali. Nel processo Eternit Bis, che si svolge davanti alla Corte d’Assise di Novara nei confronti di Stephan Schmidheiny, accusato dell’omicidio volontario, con dolo eventuale, di 392 casalesi e monferrini, dipendenti Eternit e no, morti a causa dell’amianto, Silvestri è stato incaricato dai pubblici ministeri Gianfranco Colace e Mariagiovanna Compare di svolgere accertamenti su modalità e livelli di esposizione alla fibra di amianto che costituiva la materia prima nel ciclo produttivo dell’Eternit di Casale (azienda gestita direttamente dall’imprenditore svizzero tra il 1976 e il 1986, quando è stata chiusa e dichiarata fallita).

I TRATTATI STORICI

Dunque, Albrecht. Nel suo «Trattato», divulgato 123 anni fa, lo scienziato spiegava chiaramente da quali polveri ci si doveva difendere, raccomandava di non uscire dal luogo di lavoro con gli abiti indossati in fabbrica (e la necessità di dotare gli opifici di spogliatoi, lavandini, bagni, armadietti doppi per non mischiare gli indumenti di lavoro con quelli che si usano fuori), raccomandava l’uso di mascherine ben aderenti al volto e riteneva indispensabile l’aspirazione delle polveri nel posto preciso in cui essa si produce.

Dieci anni dopo Albrecht, la Società Industriali d’Italia per la Canapa e la Juta pubblicò il volume «Sicurezza e igiene nella filatura di canapa e juta» a cura dell’ingegner Pontiggia. E anche qui si parla di polveri e di come mettersi al riparo.

Ma ancor più illuminante e profondamente attuale il testo di Giovanni Loriga, docente universitario di Igiene industriale, divulgato nel 1910 e ripubblicato nel 1938. In cinque postulati sono riassunti i fondamentali mezzi di difesa contro le polveri. Il dottor Silvestri, nell’udienza del 22 ottobre, li ha illustrati alla Corte d’Assise presieduta da Gianfranco Pezone (affiancato dal giudice Manuela Massino e dai sei popolari).

I CINQUE POSTULATI

Vale la pena riportare quanto raccomandava categoricamente Loriga: «Impedire la produzione delle polveri (o usando materiali che non le producono oppure bagnando i materiali polverosi o le polveri stesse); impedirne la dispersione, utilizzando apparecchi chiusi o comunque evitando il contatto diretto dell’operaio; raccogliere la polvere nel momento e nel luogo in cui si produce; ventilare l’ambiente per diminuire la quantità di polvere che può entrare in contatto con l’operaio; se questo non basta, proteggere con mezzi idonei la pelle, gli occhi e gli organi di respirazione». Loriga pose l’accento altresì sul pericolo reale di diffondere le polveri all’esterno delle fabbriche.

La considerazione del consulente Silvestri è semplice: «Non c’è da inventare molto rispetto a quanto prefigurato oltre cento anni fa».

E, invece, quei vademecum di scienza, coscienza e buon senso – «tutti scritti in chiaro italiano» ha ribadito Silvestri) non furono tenuti in grande considerazione, altrimenti non si sarebbe qui, oggi, a celebrare un processo per la morte di centinaia di persone che quella polvere d’amianto l’hanno respirata: dentro e fuori dalla fabbrica. Ed è stato fatale.

IL RUOLO DEL «SIL»

Ma come si è potuta consentire una disinvolta e prolungata diffusione di fibra mortale, che si sapeva cancerogena sicuramente da metà degli anni Sessanta del secolo scorso?

Il consulente ha evidenziato che, in effetti, l’Eternit nel 1975-76 aveva costituto il Sil, l’organismo aziendale che si occupava di igiene e lavoro, strettamente connesso all’Asbestos Institute tedesco di Neuss, diretto dal professor Robock, di fama internazionale, scienziato di fiducia di Schmidhieny. Il Sil eseguì negli anni parecchi campionamenti per accertare la presenza e la concentrazione della polvere di amianto nello stabilimento casalese, ma, a parere del consulente che ha esaminato tutta la documentazione disponibile, «si ritiene che la situazione rappresentata dall’Eternit, tramite l’attività del Servizio di Igiene e Lavoro, non sia stata veritiera e, in realtà, ci sia stato un inquinamento più elevato e diffuso di quanto l’azienda abbia dichiarato». A dire che, in particolare, «è difficilmente verificabile l’accuratezza dei monitoraggi eseguiti dal Sil; non ne sono stati eseguiti negli spogliatoi, in mensa e in condizioni particolari come manutenzioni, incidenti e infortuni igienistici, in orario notturno, durante le operazioni di pulizia e durante le operazioni di frantumazione degli scarti con pala meccanica». Inoltre, «non risultano documenti che indichino la destinazione degli sfridi (il cosiddetto polverino)».

IL CORSO DI FORMAZIONE

Il professor Silvestri ha invece recuperato notizia (tra le carte depositate al processo, ormai definito, contro l’Amiantifera di Balangero) di un «corso di formazione per tecnici dirigenti, tenuto dal professor Robock a dicembre 1976, a Neuss. «Furono impartite disposizioni su come far fronte a eventi eccezionali». Di che tipo, ad esempio? «Il rifiuto di un operaio di accedere al posto di lavoro ritenuto nocivo», oppure come comportarsi all’«arrivo di giornalisti, sindacati, enti pubblici, sindacati, ecc».

E come erano tenuti a regolarsi i dirigenti tecnici in base alle istruzioni impartite al corso di formazione? «E’ consigliabile – fu detto loro -, nei contatti con le organizzazioni sindacali, mediche e statali italiane, a proposito degli standard di polverosità riferirsi alla legislazione tedesca o americana, che sono meno restrittive»: cioè consentivano la concentrazione di 2 fibre per centimetro cubo. Perché, invece, «la concentrazione di 0,5 fibre per centimetro cubo (su cui si era incentrata in quel momento la discussione in Italia, ndr) non è stata accettata perché l’industria dell’amianto ha risposto che non potrebbe adeguarsi e sarebbe obbligata a chiudere».

Ancora una raccomandazione ai dirigenti tecnici, a chiusura del corso: «Dissociarsi, in ogni discussione, dal pensiero del dottor Selikoff». Lo scienziato che, a inizio anni Sessanta, aveva dichiarato al mondo che l’amianto è cancerogeno e fa morire non soltanto chi lo lavora.

SOVRAPPREMIO ALL’INAIL

Che la polvere d’amianto fosse nociva lo dimostra anche il fatto che le aziende che utilizzavano questo minerale dovevano pagare all’Inail un sovrappremio (erano diciassette in tutta la provincia di Alessandria: chi, come l’Eternit, lo impiegava in modo massiccio come materia prima, chi nel proprio ciclo produttivo usava materiali o strumenti che contenevano amianto).

«In base alla legge 780 del 1975, furono modificati i criteri di conteggio del sovrappremio, con la conseguenza che sarebbero aumentate considerevolmente le somme dovute dall’Eternit all’Inail» ha spiegato Silvestri.

A meno che? «A meno che – ha proseguito il consulente – si fosse riusciti a dimostrare che la concentrazione di polveri all’interno del posto di lavoro fosse al di sotto di 1000 fibre per litro»: cioè la metà del valore limite di soglia proposto dall’Enpi (Ente nazionale prevenzione infortuni) in quell’epoca.

L’Eternit di Casale portò all’Inail di Roma i risultati dei rilievi effettuati dal proprio Sil che attestavano una concentrazione di fibre inferiore a quella soglia. L’Inail ci credette e ridusse notevolmente l’importo del sovrappremio a carico dell’azienda.

LE RENDITE DI PASSAGGIO

Se ne accorsero sindacati e lavoratori a Casale quando alcuni operai si videro negare la cosiddetta «rendita di passaggio». Di che si tratta? Il principio è questo: chi era affetto da asbestosi (malattia causata da elevato accumulo per prolungata esposizione alla polvere), avrebbe dovuto lavorare in un luogo esente da fibra, ma non poteva farlo all’Eternit in quanto l’amianto, lì, era materia prima di produzione; dovendo lasciare il posto di lavoro (per la certificazione di «non idoneità» rilasciata dal medico di fabbrica), aveva diritto appunto alla «rendita di passaggio», equivalente a un anno di stipendio, per avere il tempo di trovare un’altra occupazione oppure di agganciarsi alla pensione. Ebbene, l’Inail di Alessandria respinse le richieste degli operai di Casale: «Non ne avete di diritto – si sentirono dire – perché la polvere è ormai al di sotto dei limiti di soglia».

Dalla Camera del Lavoro partirono diverse cause avanti al pretore Giorgio Reposo. Fu in quella occasione che il giudice incaricò il professor Michele Salvini dell’Università di Pavia di verificare come stavano le cose. E’ il più volte raccontato episodio del perito che si fece dare una scaletta su cui salì per andare a setacciare, con molta facilità, la polvere annidata a oltre un metro e mezzo d’altezza e sfuggita alle pur scrupolose manovre di pulizia fatte eseguire prima dell’ispezione.

Di amianto ce n’era ancora oltre i limiti: così il pretore riconobbe agli operai il diritto della «rendita di passaggio». Oltre a fornire indicazioni precise ai fini della sentenza di Reposo, la perizia di Salvini divenne (anche per altri processi a venire) un riferimento autorevole sulle reali condizioni ambientali della fabbrica casalese al Ronzone.

AMIANTIFERI PREOCCUPATI

Ma la discussione su concentrazioni più stringenti di fibra di amianto negli ambienti di lavoro preoccupava non poco, a fine anni Settanta, gli industriali amiantiferi. C’è traccia di questi timori su un foglietto, con appunti manoscritti, «che io ho reperito» ha detto Silvestri, tra montagne di fogli recuperati nell’archivio dell’Amiantifera di Balangero. Dà conto di una riunione che si tenne il 17 novembre 1978 alla sede di Assocemento a Roma. Viene espressa la preoccupazione dei soci Ania, l’Associazione dei produttori di amianto, er la ventilata promulgazione di una legge sull’amianto; ma il dirigente di Eternit, Costa, fa sapere che il ministro dell’epoca si impegna a nominare alti dirigenti dei settori Lavoro, Industria e Sanità «per esaminare le proposte di regolamento sull’amianto e il decreto si farà comunque di concerto con i rappresentanti di categoria». Nello stesso foglietto manoscritto si evidenzia che Confindustria, al suo massimo livello, è intervenuta anche presso l’Enpi «per rallentare la promulgazione di una normativa sui limiti di concentrazione delle fibre di amianto».

«Non so chi abbia scritto quel foglietto, non c’è una firma, non una carta intestata né un timbro – ha ammesso Silvestri – ma la conferma della sua validità sta nei fatti. I valori limite proposti dall’Enpi nel 1978 non sono mai stati tradotti in provvedimenti normativi. La Direttiva Cee 477 che introduceva il limite di 1000 fibre per litro di amianto crisotilo e di 200 fibre per litro di crocidolite o misti è stata recepita soltanto ad agosto 1991. Qualche opera sottobanco è servita – ha chiosato -: quella riunione ha ritardato di 13 anni l’introduzione dei valori limite nel nostro Paese».

CLASSIFICAZIONE MESOTELIOMI

Fin qui si è detto della scrupolosa attenzione manifestata, fin da oltre un secolo fa, dagli scienziati sulla diffusione delle polveri in quanto nocive, nel caso dell’amianto cancerogene e mortali.

La fibra di amianto, sottilissima e invisibile all’occhio, manifesta la propria virulenta malvagità figliando il mesotelioma, «una neoplasia ad alta frazione eziologica (il cui rischio, cioè, è fortemente riconducibile alla esposizione specifica ad amianto, ndr) che è oggetto di sorveglianza epidemiologica dal 1988: la raccolta dei dati sull’insorgenza della malattia consente di stimarne l’incidenza per programmare interventi di sanità pubblica».

Di questo ha parlato Alessia Angelini, nella seconda parte della relazione. Angelini, incaricata della consulenza insieme a Silvestri, è ingegnere chimico; dopo aver lavorato come ispettore sui luoghi di lavoro, è attualmente in forze all’Istituto di prevenzione oncologica della Toscana (come lo è stato Silvestri), si occupa della gestione del processo di bonifica e smaltimento di amianto per conto della Regione e della classificazione dei mesoteliomi secondo le linee guida impartite dal Registro nazionale dei mesoteliomi nel 2003.

«Si parte dalla rilevazione diagnostica – ha spiegato la consulente – e, una volta accertata la diagnosi, si procede con la valutazione anamnestica, tramite intervista diretta al paziente (o a un famigliare) e realizzata con l’aiuto di un questionario standardizzato».

«I dati – ha aggiunto Angelini – vengono immessi annualmente nei Registri regionali dei mesoteliomi e convergono poi nel Registro nazionale (ReNaM). L’Inail pubblica, periodicamente, un rapporto descrittivo basato principalmente sull’andamento della numerosità dei casi associati a vari parametri, fra cui i settori produttivi, le aree geografiche e la classificazione degli stessi secondo la definizione dell’esposizione. L’ultimo è stato divulgato nel 2018 (con riferimento alla casistica insorta fino al 2015); è attualmente in preparazione il 7° Report».

PROFESSIONALE, FAMIGLIARE, AMBIENTALE

Ne è scaturita questa suddivisione: il 70 per cento dei mesoteliomi ha origine professionale (e, di questi, l’87% per cento uomini e il 13% donne), il 4,9% ha origine famigliare (e, di questi, il 14,5% uomini e l’85,5% donne: «Non era neppure necessario scuotere la tuta, bastava la vicinanza all’operaio al suo rientro a casa con gli abiti da lavoro o i capelli impolverati» ha precisato Angelini); il 4,4% ha origine ambientale, l’1,5% extralavorativa; il residuo 19,9% è riconducibile a esposizione ignota (non si hanno informazioni sull’esposizione) o improbabile (non si riesce a individuare la fonte precisa di esposizione). «Si tratta di una classificazione di tipo qualitativo, ossia riferita alla fonte di esposizione e non alla sua durata, frequenza o intensità».

Riguardo agli «ambientali» (cioè chi si ammala di mesotelioma senza aver mai lavorato l’amianto o senza aver convissuto con un lavoratore del settore), la consulente ha riferito che «l’80% dei casi è distribuito in quattro siti italiani: Casale, Broni, Bari e Biancavilla». Nelle prime tre località c’erano stabilimenti per la produzione di manufatti contenenti amianto (Eternit e Fibronit), a Biancavilla (Catania) c’era la cava di Monte Calvario da cui si estraeva fluoroedenite, una particolare tipologia di amianto.

GLI «AMBIENTALI» A CASALE

«L’Eternit a Casale ha prodotto moltissimi mesoteliomi professionali, diversi mesoteliomi famigliari e ha esportato in modo molto più pesante che altrove il rischio di esposizione nell’ambiente cittadino, cioè fuori dalla fabbrica» ha spiegato l’ingegner Angelini.

Perché?

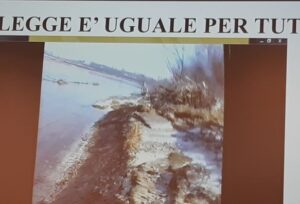

«Perché l’Eternit aveva sorgenti di inquinamento ambientale molteplici». Esempi: «La circolazione della materia prima e del prodotto finito su strada, attraversando ampie zone cittadine: dalla stazione ferroviaria ai magazzini di deposito in piazza d’Armi e allo stabilimento del Ronzone e viceversa, dai magazzini alle varie direzioni per la vendita dei manufatti, dall’arrivo dalla cava di Balangero di una parte della materia prima nei cassoni dei camion, dall’arrivo di scarti di produzione da fuori Casale fino all’area Ex Piemontese (quasi prospiciente lo stabilimento) per la frantumazione degli scarti che avveniva a cielo aperto. Altre sorgenti: la distribuzione o vendita ai privati del polverino, derivante dagli sfridi di lavorazione e contenente crocidolite (il più pericoloso «amianto blu», con potenza cancerogena cento volte superiore a quella del crisotilo o «amianto bianco»); la discarica «Bagna» sulla riva sinistra del Po, in argine Morano, dove venivano smaltiti gli scarti ormai del tutto inutilizzabili; i «ventoloni» che espellevano aria contaminata senza filtri dall’interno all’esterno dello stabilimento; le abitudini del contesto sociale (gli operai che uscivano dalla fabbrica ben tre volte al giorno, con tuta e capelli impolverati, si fermavano al bar, alla bottega, al circolo del dopolavoro o a far visita aiparenti) e la formazione della cosiddetta «spiaggia», dovuta agli scarichi, in sponda destra del fiume, di acque sporche e fanghi del ciclo produttivo.

«PASSEGGIATA» SULLA SPIAGGIA

A proposito della spiaggia lungofiume. La consulente ha proposto una passeggiata virtuale in quell’area, proiettando sullo schermo un video realizzato nel 1996, prima della bonifica, dal dottor Silvestri («di mia iniziativa»), che si era recato personalmente nel luogo per rendersi conto della situazione, accompagnato da Bruno Pesce (già segretario della Camera del lavoro di Casale e tuttora tenace portavoce nell’Associazione famigliari e vittime amianto Afeva) e da Giampaolo Bernardi, ex operaio dell’Eternit e strenuo attivista antiamianto, morto di mesotelioma.

Sulla proiezione del filmato è scaturita una schermaglia tra l’avvocato Guido Carlo Alleva (difensore dell’imputato, insieme al collega Astolfo Di Amato) e il pm Colace, non tanto nel merito di quanto illustrato dalle immagini della pluricitata «spiaggia» (vivide, come mai viste prima, e su cui veniva facile immaginare le spensierate «domeniche bestiali» di tanti casalesi in costume da bagno e picnic), ma sulla acquisizione formale del documento da parte della corte.

CONCLUSIONI

«Mai nulla è stato fatto per contrastare l’esposizione al rischio o, almeno, per limitarla» ha concluso la consulente Angelini. Ecco perché Casale è un caso emblematico per i mesoteliomi ambientali. «Che l’amianto era cancerogeno lo si sapeva – ha incalzato la consulente – ma non si è fatto nulla per contenere le emissioni all’interno e all’esterno della fabbrica». Sia per tutto il tempo di produttività della fabbrica sia dopo la chiusura nel 1986: «L’Eternit non ha contribuito e collaborato con le autorità né per indicare i siti contaminati né partecipando alle bonifiche del polverino e ha lasciato la fabbrica in un tremendo stato di manutenzione. Le bonifiche sono state interamente finanziate con soldi pubblici italiani. Tutto questo – è stata la conclusione lapidaria – ha contribuito ad aumentare il rischio amianto nella popolazione». Oggi chi si ammala di mesotelioma (ancora al ritmo impressionante di una cinquantina di nuovi casi all’anno) sono quasi totalmente cittadini estranei alla fabbrica del Ronzone.

E LE ALTRE FABBRICHE?

«Ma a Casale c’era soltanto l’Eternit che utilizzava l’amianto?» si è informato il presidente Pezone. «Era l’unica azienda che lo adoperava come materia prima nel ciclo produttivo – ha risposto Silvestri -. Altre usavano materiali contenenti amianto, ma ne erano utilizzatori indiretti e non inquinavano verso l’esterno».

Il presidente della Corte, incerto, ha dettagliato la domanda: «Non c’era a Casale anche la Fibronit?». E il consulente: «La Fibronit aveva stabilimenti a Broni e a Bari».

E a Casale no?

No, a Casale la Fibronit aveva la sede legale, prima Cementeria Italiana Fibronit, poi Fibronit spa, poi Finanziaria Fibronit spa (con intera partecipazione anche in un terzo polo produttivo in provincia di Matera, la Materit srl a Ferrandina). La Fibronit, che aveva a Casale solo gli uffici in via Mameli, fu dichiarata fallita il 13 marzo 2003.

PROSSIMA UDIENZA

Il processo Eternit Bis prosegue lunedì 25 ottobre: saranno ascoltati una ventina di famigliari delle vittime, costituiti parte civile, e anche il segretario regionale della Cgil Massimo Pozzi.

Traduzione a cura di Vicky Franzinetti

October the 22nd Hearing – Eternit bis trial by SILVANA MOSSANO

Is breathing in dust bad for you? Yes, it is. Is spreading dust inside and outside the workplace bad? Yes, it is. Are there precautions that can be taken? Yes, there are.

Photo: Expert witnesses Stefano Silvestri and Alessia Angelini

In his powerful “Treatise on Industrial Hygiene” published in 1898, Heinrich Albrecht from Vienna (1866-1922) wrote as much. “It was translated from German into Italian”, pointed out Stefano Silvestri, an occupational hygienist with particular expertise in the field of asbestos, former employee of the Institute for Cancer Prevention of Tuscany, member of several Government committees on ministerial commissions, expert witness in several court cases on environmental crimes. In the Eternit Bis trial, being held before the Novara Court of Assizes against Stephan Schmidheiny, accused of wilful murder, of 392 people from Casale and Monferrato, Eternit employees and community members, who died from asbestos, Silvestri was appointed by prosecutors Gianfranco Colace and Mariagiovanna Compare to research into the methods and levels of exposure to asbestos fibre, which was the raw material used in production at the Casale Eternit (a company directly managed by the Swiss entrepreneur between 1976 and 1986, at which point it was closed and filed for bankruptcy).

ANCIENT TREATISES

In his 123 years old text, Albrecht clearly explained which dust was dangerous and required protection. He recommended not leaving the workplace wearing factory overalls – and thus the need for plants to have changing rooms, wash basins, bathrooms and double lockers so as not to mix work clothes with those worn outside, recommended the use of masks that fit tightly around the face and considered it essential to extract dust where it was produced.

Photo: A portable dust extractor of an older generation, but already envisaged many decades ago

Ten years after Albrecht, the Società Industriali d’Italia per la Canapa e la Juta published a book entitled ‘Sicurezza e igiene nella filatura di heapa e la juta’ (Safety and hygiene in hemp and jute spinning), published by engineer Pontiggia. Here too, there is talk of dust and how to protect oneself, but even more relevant and highly topical is a text by Giovanni Loriga, a university lecturer in industrial hygiene, published in 1910 and republished in 1938. Five postulates summarise the fundamental means of defence against dust. At the hearing on 22 October, Dr Silvestri illustrated them to the Assize Court chaired by Gianfranco Pezone (assisted by Judge Manuela Massino and six jurors or popular judges).

THE FIVE POSTULATES

It is worth recalling what Loriga categorically recommended: ‘Prevent the production of dust (either by using materials that do not produce it or by wetting the dusty materials or the dust itself); prevent its dispersion, using closed equipment or in any case avoiding direct contact with the worker; gather the dust at the time and in the place where it is produced; ventilate the environment to reduce the amount of dust that can come into contact with workers; if this is not enough, protect the skin, eyes and breathing organs with suitable means’. Loriga also emphasised the real danger of spreading dust outside plants.

Photo: An old grinder

Consultant Silvestri’s remark is simple: “There’s not much needed compared to what was said over a hundred years ago”.

Instead of using the warnings of science, conscience and common sense – “all written in plain Italian,” Silvestri reiterated – were not taken into great consideration, otherwise we would not be here today, holding a trial for the deaths of hundreds of people who breathed in that asbestos dust: inside and outside the factory. And it was fatal.

THE ROLE OF The SIL

How could an unrestrained and prolonged spread of the deadly fibre known to be a carcinogenic, since the mid-1960s, have been allowed? Silvestri pointed out that, in 1975-76, Eternit had set up SIL, the company department in charge of hygiene and work, closely linked to the German Asbestos Institute in Neuss, directed by Professor Robock, an internationally renowned scientist trusted by Schmidhieny. Over the years, SIL carried out several samplings to ascertain the presence and concentration of asbestos dust in the Casale plant, but, in the expert who has examined all the available documentation said ” the picture represented by Eternit, through the activities of SIL, the Occupational Hygiene Service, appears not to be faithful and, in fact, there was a higher and more widespread pollution than the company declared”. In particular, ‘it is difficult to verify the accuracy of the monitoring carried out by SIL; no testing was carried out in the changing rooms, in the canteen and in special conditions such as maintenance, accidents and hygiene incidents, at night, during cleaning operations and during waste crushing operations with a mechanical shovel’. Furthermore, ‘there are no documents indicating the destination of the waste (the so-called dust)’.

THE TRAINING COURSE

On the other hand Silvestri has recovered information (among the papers filed in the now finalised trial against Amiantifera Balangero) of a “training course for technical managers, held by Professor Robock in December 1976, in Neuss. “Instructions were given on how to deal with exceptional events”. What kind, for example? “The refusal of a worker to enter the workplace deemed to be harmful”, or how to deal with the “arrival of journalists, trade unions, public bodies, etc”.

And how were the technical managers to deal with the instructions given at the training course? It is advisable,” they were told, ” to refer to German or American legislation on dusting standards, which are less restrictive in contacts with Italian trade union, medical and state organisations, “, i.e. they allowed a concentration of 2 fibres per cubic centimetre. Because, instead, ‘the concentration of 0.5 fibres per cubic centimetre (on which the discussion in Italy was focused at that time, ed.) was not accepted because the asbestos industry replied that they could not adapt and would be forced to close’. Another one of Robock’s recommendation to the technical managers at the end of the course: ‘In any discussion, disassociate yourself from Dr Selikoff’s thinking’. Selikoff was the scientist who, had declared to the world that asbestos is carcinogenic and causes death not only to those who work with it at the beginning of the 1960s.

HIGHER BENEFITS TO INAIL (the National Workers’ Compensation Fund)

The fact that asbestos dust was harmful was also demonstrated by the fact that companies that used this mineral had to pay INAIL a higher benefit: there were seventeen in the whole province of Alessandria: those who, like Eternit, used it on a massive scale as a raw material, and those who used materials or tools containing asbestos in their production cycle. “Pursuant Law 780 of 1975, the criteria for calculating the higher benefits were changed, with the result that the sums owed by Eternit to Inail would have increased considerably,” Silvestri explained. “Unless”, continued the consultant, “they had been able to demonstrate that the concentration of dust in the workplace was below 1000 fibres per litre”, i.e. half of the threshold limit value proposed by Enpi (National Accident Prevention Agency) at the time. Casale’s Eternit company brought the results of its own SIL’s measurements to INAIL in Rome, which showed a fibre concentration below the threshold value. Inail accepted the measurements and considerably reduced the amount of the higher benefits to be paid by the company.

BRIDGING PENSIONS

Trade unions and workers in Casale at one point were denied the so-called ‘bridging pensions’. What is it? This was the principle: asbestosis sufferers (a disease caused by high accumulation due to prolonged exposure to asbestos dust), needed to work in a place free of fibre, but could not do so at Eternit because asbestos was a raw material required for production. If the company doctor were to certify the were no longer fit to work they were entitled to a ‘bridging pension’, equivalent to one year’s salary, to have time to find another job or to retire if of the age. Well, Alessandria’s INAIL rejected the requests of the workers of Casale: “You are not entitled to it,” they were told, “because the dust is now below the threshold limits”.

Photo: The Casale Eternit plant

The Unions took several cases were taken before the Courts (magistrate Giorgio Reposo). It was on that occasion that the judge appointed Professor Michele Salvini of the University of Pavia to verify data. This is when the well known episode of Prof Salvini who went up a ladder to gather the dust at one and a half metres, which had escaped the careful cleaning operations carried out before the inspection. Asbestos levels were still beyond the limits, and so the magistrate granted the workers the right to a “bridging pension (rendita di passaggio)“. As well as providing precise information for Judge Reposo, Salvini’s report became an authoritative reference point on the actual environmental conditions of the Ronzone factory in Casale to be used in trials to come.

THE ABSESTOS INDUTRY BECOMES CONCERNED

In the late 1970s, the asbestos industry became very concerned about on more strictly monitored concentrations of asbestos fibres in the workplace. Silvestri found a trace of these fears on a sheet of paper, in handwritten notes, “that I found,” said Silvestri, “amidst mountains of papers recovered from the archives of the Balangero Asbestos Mine (Amiantifera in Balangero). It refers to a meeting held on 17 November 1978 at the headquarters of Assocemento in Rome. At the meeting Ania members, the Association of Asbestos Producers, expressed concerns about over the proposed asbestos law. However, Costa, the Eternit manager, informed the meeting that the Minister of the time promised to appoint senior managers from the Labour, Industry and Health sectors “to examine the asbestos bills and the decree. He also added that any decision would be made in consultation with the representatives of the industry”. The same handwritten note stated that the leadership of the Confederation of Industrialists (Confindustria), had also intervened with ENPI ‘to slow down the introduction of legislation on asbestos fibre concentration levels’. “I don’t know who wrote that piece of paper, there is no signature, no letterhead and no stamp,” Silvestri admitted, “but the confirmation of its validity lies in the facts. The limit values proposed by ENPI in 1978 never became part of the law. The then EC (now EU) Directive 477, which introduced a limit of 1,000 fibres per litre of chrysotile asbestos and 200 fibres per litre of crocidolite or mixed asbestos, was incorporated only in August 1991. Some underhand work was needed,” he said, “and that meeting delayed the introduction of the limit values in our country by 13 years.

MESOTHELIOMA CLASSIFICATION

So far we have only referred to the scrupulous attention scientists started paying over a century ago, to the spread of dust, and in the case of asbestos as carcinogenic and deadly.

Photo: Expert witness Alessia Angelini

The asbestos fibre, which is very thin and invisible to the eye, manifests its virulent viciousness by producing mesothelioma, “a neoplasm with a high etiological fraction (i.e. the risk of which is strongly linked to specific exposure to asbestos, ed.) that has been the subject of epidemiological surveillance since 1988: the collection of data on the onset of the disease makes it possible to estimate its incidence in order to plan public health interventions”.

The next expert witness, Dr Alessia Angelini spoke about this in the second part of her report: Angelini is a chemical engineer; after having worked as labour inspector , she is currently working for the Institute of Oncological Prevention of Tuscany (as was Silvestri), and is in charge of managing reclamation and disposal of asbestos on behalf of the Region and of the classification of mesotheliomas according to the guidelines issued by the National Mesothelioma Registry in 2003.

“We start with the diagnostic survey,” Angelini explained, “and once the diagnosis has been made, we proceed with the case history, through direct interviews with the patient (or a family member) and carried out with the help of a standardised questionnaire.

“Data- added Angelini, -are entered annually in the Regional Mesothelioma Registers and then pooled in the national register (ReNaM). Inail periodically publishes a report based mainly on the trend in the number of cases associated with various parameters, including production sectors, geographical areas and the classification of cases according to the definition of exposure. The last one was released in 2018 (with reference to cases arising up to 2015); the 7th Report is currently being prepared”.

OCCUPATIONAL, FAMILY, & ENVIRONMENTAL MESOTHELIOMA CASES

The result is this breakdown: 70% of mesotheliomas have an occupational origin (and, of these, 87% men and 13% women), 4.9% have a family origin (and, of these, 14.5% men and 85.5% women): “It was not even required to shake the overalls, it was enough to be close to the worker when he returned home with his work clothes or dusty hair,” Angelini pointed out); 4.4 per cent of the cancers had an environmental origin, 1.5 per cent a non work related origin; the remaining 19.9 per cent was attributable to unknown exposure (no information on exposure is available) or unlikely exposure (the precise source of exposure cannot be identified). “This is a qualitative classification, i.e. referring to the source of exposure and not to its duration, frequency or intensity”.

As for the ‘environmental cases’ (i.e. people who develop mesothelioma without ever having worked with asbestos or without having lived with a worker in the sector), the consultant reported that ‘80% of the cases were scattered over four Italian sites: Casale, Broni, Bari and Biancavilla’. In the first three locations there were factories for the production of products containing asbestos (Eternit and Fibronit), in Biancavilla (Catania) there was the Monte Calvario quarry from which fluoroedenite, a particular type of asbestos, was extracted.

THE ‘ENVIRONMENTAL CASES’ IN CASALE

“Eternit in Casale produced a large number of occupational mesotheliomas, several family mesotheliomas, and exported the risk of exposure to the city environment, i.e. outside the factory, much more heavily than elsewhere,” Angelini explained. Why was that? “Because Eternit had multiple sources of environmental pollution. Examples: “The circulation of raw materials and finished products by road, crossing large areas of the city: from the railway station to the storage warehouses in Piazza d’Armi and the Ronzone plant and vice versa, from the warehouses to the various directions for the sale of the products, from the arrival of part of the raw material from the Balangero quarry in the lorry boxes, from the arrival of production waste from outside Casale to the former Piemontese area (almost opposite the plant) for the crushing of the waste, which took place in the open air. Other sources: the distribution or sale to private individuals of the powder, deriving from processing waste and containing crocidolite (the most dangerous “blue asbestos”, with a carcinogenic potency a hundred times greater than that of chrysotile or “white asbestos”); the “Bagna” landfill on the left bank of the Po, on the Morano embankment, where the waste, now completely unusable, was disposed of; the “fans” that expelled contaminated air without filters from inside to outside the factory; the social habits (the workers left the factory three times a day, wearing dusty overalls and hair, and stopped at the bar, the shop, the after-work club or to visit relatives) and the formation of the so-called “beach”, due to the discharge of dirty water and sludge from the production cycle on the right bank of the river.

THE ‘PROMENADE’: STROLLING ALONG THE BANKS OF THE RIVER

About the riverside beach. Angelini proposed a virtual walk in that area, projecting a video Silvestri made in 1996, before the reclamation, (“on my own initiative”). Silvestri had personally gone there to get an idea of the situation, accompanied by Bruno Pesce (former secretary of the CGIL Union of Casale and still tireless spokesperson for Afeva (the Association of Asbestos Victims and Families) and Giampaolo Bernardi, a former Eternit worker and strenuous anti-asbestos activist, who died of mesothelioma.

Photo: A view of the “beach” on the left bank of the Po, taken from the film shot in 1996 by Stefano Silvestri

A skirmish broke out between the defence lawyer Guido Carlo Alleva (defending with his colleague Astolfo Di Amato) and the prosecutor Colace over the showing of the film, not so much on the merits of the images of the “beach” (vivid, as never seen before, and on which it was easy to imagine the carefree “beastly hot Sundays” of many people from Casale in bathing suits and picnics), but on the formal acquisition of the document by the court.

Photo: A view of the “beach” on the left bank of the Po, taken from the film shot in 1996 by Stefano Silvestri

Photo: Lawyers and prosecutors at the hearing on 22 October 2021 of the Eternit Bis trial

CONCLUSIONS

“Nothing was ever done to counteract exposure to risk or, at least, to limit it,” concluded Angelini. This is why Casale is an emblematic case for environmental mesotheliomas. “It was a known fact that asbestos was carcinogenic,” the expert continued, “but nothing was done to contain emissions inside and outside the factory. Throughout the factory’s productive period and after its closure in 1986: “Eternit did not contribute and cooperate with the authorities by indicating contaminated sites or by participating in the clean-up of the dust and left the factory in a terrible state of repair. The clean-ups were entirely financed with Italian public money. All this,” she concluded briefly, “has contributed to increasing the asbestos risk in the population. Today, those who fall ill with mesothelioma (still at the impressive rate of about fifty new cases a year) are almost entirely citizens who did not set foot in the Ronzone plant.

WHAT ABOUT THE OTHER PLANTS?

“Was Eternit the only factory that used asbestos in Casale?” inquired President Pezone. “Others used materials containing asbestos, but they were indirect users and did not pollute the outside world. The main judge detailed the question: ‘Wasn’t Fibronit also in Casale? And the expert witness replied : ‘Fibronit had plants in Broni and Bari’. And not in Casale? No, Fibronit had its registered Headquarters in Casale, first Cementeria Italiana Fibronit, then Fibronit spa, then Finanziaria Fibronit spa (with full participation in a third production site in the province of Matera, Materit srl in Ferrandina). Fibronit, had offices in Casale in Via Mameli, was declared bankrupt on 13 March 2003.

NEXT HEARING

The Eternit Bis trial will continue on Monday, October 25: about twenty families of the victims will be heard and Massimo Pozzi , regional CGIL Union secretary.

Photo: Picket outside the courtroom of the University of Novara where the Eternit Bis trial is taking place. As well as the Afeva activists, on Monday 22 October there was also a large delegation from Legambiente.

Grazie mille Silvana! per il tuo puntuale costante ed ottimo resoconto: molto utile per chi non può partecipare alle udienze e per la …storia.

Complimenti Silvana di quante cose ci informi che non conoscevamo se non solo la pericolosità della malattia e il suo decorso nefasto. Grazie continua così per il bene della comunità e della

Nazione. Bisogna conoscere “prima”’e se si sa : parlare , denunciare all’autorità competente . Buona Domenica. Ciao Paolo